A friend of mine who works in advertising has a theory that American civilization began its decline when ads began to feature regular schlubs as the main characters in television commercials. The way he puts it, up until the late 1990’s TV commercials were mostly aspirational affairs, featuring fashionably-dressed, healthy-looking folks peddling whatever product they happened to be peddling. You too could be like one of these beautiful, well-adjusted people if only you washed your drawers with Tide or sipped Sunny Delight for breakfast. But somewhere around the end of the twentieth century, the big brains of Madison Avenue decided that the more relatable Everyday Joe approach was the way to go - that you’re more likely to buy the new lime-flavored Tostitos if the person hawking them on your television screen looks a lot like you or your dipshit neighbor. And without the guidance and inspiration of our more refined TV pitchmen and women, it’s only a short descent to marathons of Here Comes Honey Boo Boo on “The Learning Channel.”

I was thinking about my friend’s theory after a recent rewatch of Peter Bogdanovich’s The Last Picture Show, one of the most beautiful and lyrical films in all of American cinema. It’s a bleak, angsty coming-of-age movie set in a dying Texas town that, despite its bleakness, treats its characters and its setting with such deep love and compassion that it’s hard not to weep.1 The film is by no means a tear-jerker - it is often very funny and its characters are brimming with life2 - but its depth of feeling is such that it made me wonder if American culture is currently capable of producing such a work.

Back when I was on Twitter (er, X), one complaint I would often see from film critics on the platform - whether of the armchair variety or those writing professionally for digital media shops - was that this or that movie was bad because it failed to relate to their own personal experience. As though the mission of a film, or of any work of art, is to provide validation to the viewer of their own experience or identity or what-have-you. When a culture has its head so far up its own ass that it can’t be bothered to engage with anything that isn’t a reflection of itself - when it demands relatability above all else - you have to wonder if it’s capable of producing a film such as Bogdanovich’s 1971 masterpiece. Or whether it even aspires to such heights.

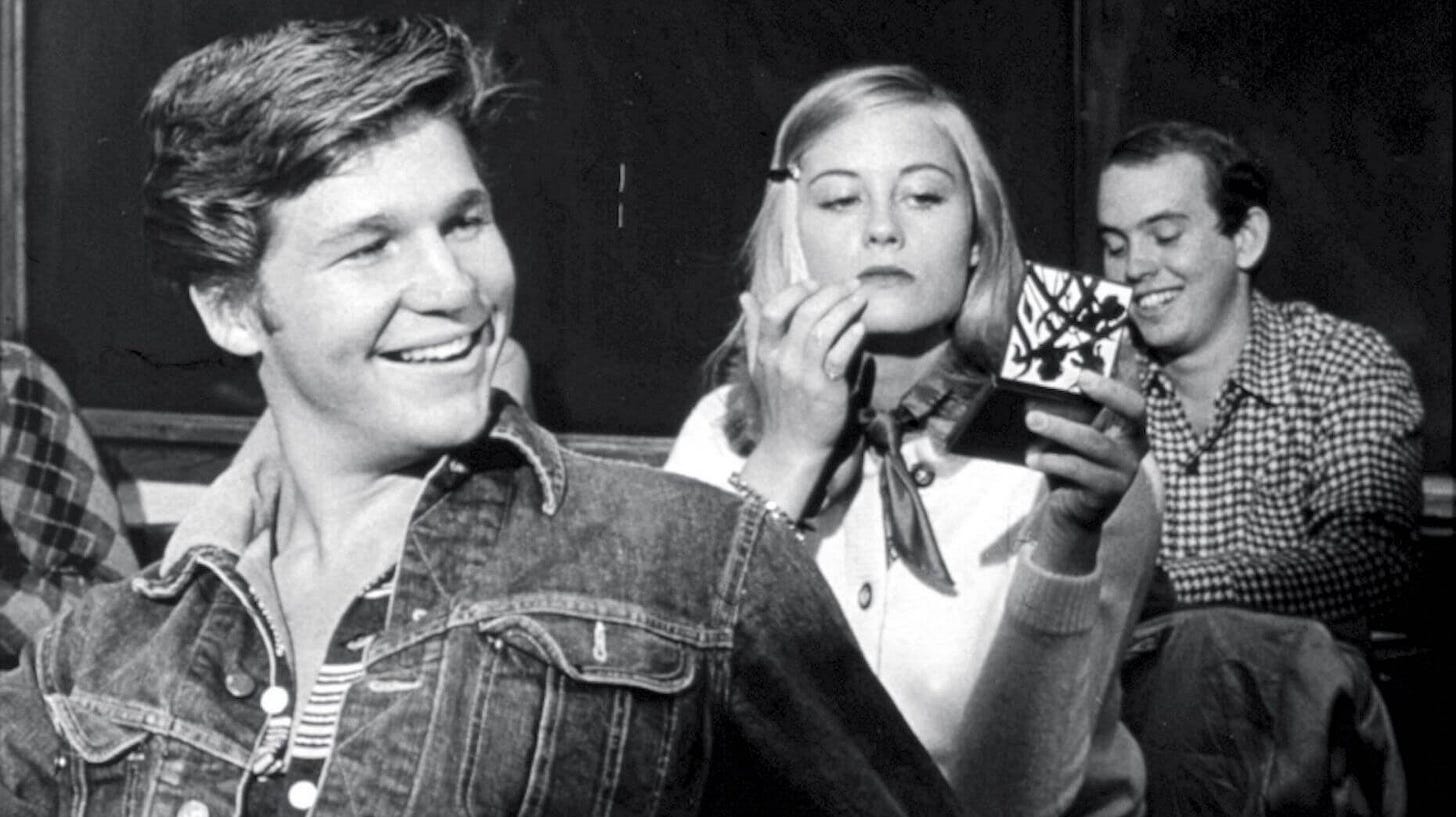

Not that there’s anything wrong with relatability per se. One of my favorite movies - also set in the Lone Star State - is Richard Linklater’s Dazed and Confused, a film I initially fell in love with partly because I identified so closely with its motley crew of stoners and losers in suburban Texas.

Much has been written about the essential plotlessness of Linklater’s second feature film, and while I’ve got nothing novel that I can possibly add to that discussion, I think the main reason Dazed and Confused endures (the film is thirty years old!) is precisely because it tells its story in such a breezy manner. You’re really just hanging out with these characters. It’s one of those films where you really couldn’t care less where the story takes you as long as it takes you there with your movie buddies. This quality is what links Linklater and Bogdanovich’s classics for me: these are two films where the characters you follow for two hours truly feel like they’re your friends.

(Yes, I’m aware that the clip above is basically a rip-off of American Graffiti, but like so what?)

When people think of teen movies, oftentimes the first thing that comes to mind is a John Hughes classic, like The Breakfast Club or Ferris Bueller’s Day Off.3 Those are fine films, to be sure, but these two Texas jewels sit firmly at the top of my list.

The fact that this movie often feels more like an Italian neorealist movie than an American film made at the outset of the 1970’s - a decade that would be characterized by free-wheeling, rebellious American cinema - is one of the most transgressive things about it.

The protagonist of The Last Picture Show - Sonny Crawford - looks exactly like what I imagine a young George W Bush would’ve looked like as a teenager. Which is a fitting comparison, as the actor who plays Sonny - Timothy Bottoms - went on to play Dubya in the short-lived Comedy Central sitcom That’s My Bush!

I’m a Weird Science man, myself. RIP, Bill Paxton.

Your article is well written... thanks.

‘The Last Picture Show’ resonates due to its ability of transferring what is happening in North Texas to virtually any locale... with the characters intact. All we had to do is substitute the characters, in the film, with our own real-life situations plus we could interchange which actor we wanted to be...

Creating this masterpiece in black and white was gutsy but if it wasn’t filmed that way, it wouldn’t have been so impactive.

I certainly hope a colourized version is never done.

Write more.

This essay is excellent, thanks!